This post is hard to read for many. We have created a podcast out of this post which is easier to consume. We suggest that you hear to the podcast first and then read this post for finer details.

WHAT IS SYSTEMS THINKING: A FRESH PERSPECTIVE

What is Systems Thinking? is the most challenging question I've encountered in my career—one I still wrestle with today.

I've invested countless hours contemplating how to answer this in a way that makes you exclaim, "Ah! Now I truly understand! Learning systems thinking is absolutely essential!" and I have not succeeded in that effort so far.

However, I am happy about one thing that in my quest for good explanation, I deliberately avoided the typical definitions you hear everywhere: "Systems thinking is the ability to think about the whole." "Systems thinking helps you deal with complex problems." And I right away rejected these common explanations for two fundamental reasons.

Problems with Common Definitions

First, these answers are solution-oriented rather than problem-oriented. They claim systems thinking transforms you into a holistic thinker or equips you to handle complexity without first establishing what's wrong with your current thinking. I don't like people who sell solutions to make my world better without telling or proving a problem to me.

Second, I find these solutions of thinking about the whole and solving for complexity very flawed. I've never met a CEO who doesn't already consider the whole of their company when making decisions. Managers at all levels think about the whole organization all the time. Many citizens of a country at times prioritize national well-being over personal gain. Frankly, I find it condescending when someone suggests people don't naturally think about the whole. The same argument applies for the assertion that Systems Thinking allows one to deal with complexity, but unless someone can prove how our current thinking is inadequate in dealing with current complexity, that statement is worth nothing and a perfect way to fool and delude people. Also, humans have been thinking and have successfully navigated complexity for centuries, so one shall not fall for the assertion that I have a thinking that I can impart that allows you to deal with complexity unless the person can make a case that our current thinking is incapable of dealing with that complexity.

So you all must be thinking, "Manish can't explain to us what Systems Thinking is and he is rightfully critical of the existing definition of Systems thinking, but as a listener who wants to know what systems thinking is, this talk has zero value when the listener wants to know what's systems thinking. So why am I listening to Manish?" Because I have a new pitch on what systems thinking is, why one shall learn it, and we want to try it on you.

The New Pitch

So here is my latest pitch, but for the pitch to be delivered we must first examine what thinking does for us and identify limitations of our current thinking if any, then seek possible ways to enhance that thinking. If any pitch on thinking fails to do that, I will term that pitch a terrible one.

If you're ready, let's dive right in and discuss three topics:

- What is thinking?

- What value does thinking provide to humans, and does our current thinking have any limitations?

- Are there additional thinking enhancements that can fill the limitations of current thinking?

Let's talk about each of them one by one.

What is Thinking?

What is thinking? At its core, thinking is our remarkable human capacity to create mental representations of the world around us. We construct these mental models to make sense of our reality, then run simulations within our minds—projecting how different actions (or inactions) might unfold.

Through this internal modeling, we predict possible future states and outcomes. Based on these predictions, we decide whether to act upon the world or not, all in pursuit of achieving our desired results. These mental models themselves can be called systems.

Regular Thinker vs. Systems Thinker

If you agree with this definition of thinking, this makes every human not only a thinker because we all think, but we also think in terms of systems. If that's the case, what's the difference between a regular thinker and a systems thinker when we all think in systems?

The difference, in my view, is that a regular thinker creates mental models, simulates those models, and makes decisions based on those simulations—but isn't aware of the thinking paradigm they're using to develop and simulate these models. A systems thinker, on the other hand, is aware of the thinking paradigm they're using to develop and simulate these mental models. The difference seems to be little but it's not. Being aware of the thinking paradigm using which we think can be a superpower and game changer.

You see, when someone is unaware of their thinking paradigm, they are also unaware of strengths and weaknesses of that paradigm. Therefore, they are not conscious of the limitations or accuracy of their mental models and simulations, to be specific limitations that emanate from the limitation of thinking paradigm which they are unaware of.

If one becomes aware of flaws of their mental model and its simulation, they can correct them as they experience mistakes or failures. But there's no way to learn from mistakes or failure, no matter how many times you experience it—if they emanate from the thinking paradigm of which we are not aware. It simply can't fit into mental models. So when people run into issues, they blame countless external factors and other people but never take responsibility for their actions. Not because of lack of intent or lack of want but because they can't, their mind will never allow them to.

Systems thinkers, on the other hand, are aware of the thinking paradigm they're using to develop mental models and simulate those models. They recognize the strengths and weaknesses of the paradigm and therefore understand the limitations of their models and simulations. They are able to consume mistakes and failures better and error correct their way out of it by taking responsibility, because their mind allows them to.

The Second-Order Effect

This creates a powerful second-order effect: Because systems thinkers are aware of the thinking paradigm they're using and its limitations, they not only incorporate failures into their thinking paradigm which they are aware of, but they actively seek newer thinking paradigms to create mental models and simulations to fit for specific situations. This gives them more decision options—options that aren't available to regular thinkers who never seek to learn new thinking paradigms, you know why? Because they are just not aware of its existence and therefore their limitations.

So the first step to becoming a systems thinker doesn't start with learning systems thinking tools and techniques—it starts with becoming aware of your current thinking paradigm and then becoming aware of its limitations. Systems thinking therefore is primarily self-awareness training, which then transforms everything from how you develop an understanding of the world around you, how you develop mental models, how you simulate them and how you make decisions.

A Practical Example

Now you must be thinking, "This makes sense in a very loopy way, but seems too academic and dense. Can you provide an example of a mental model that you have that's incorrect and there is no way for you to correct it because the problem is in your thinking paradigm which you are not aware of?"

That is exactly what we are about to do next. But before we do, consider HOW challenging your request is: to make you prove that the thinking paradigm which you use and are not even aware exists is flawed. Because if we are successful in that effort, then we will have to make you aware of the thinking paradigm first, which we can't just do in minutes. That's what we do in our courses. If that's not possible, how can I prove something is flawed if you are not aware of that something? So you understand it's a very hard thing to do, but we have devised a clever trick just to do that. To achieve that, we will have to answer a question like the one that you get in your SAT or high school exam. Here is the question.

The Ship Rope Problem

You work on a ship that is 2000 feet long from bow to stern. The captain wants to tie a rope from bow to stern so that it's taut (very tight). He asks you to get a 2000-foot rope and secure it across the two ends of the ship.

You order the rope, but when it arrives and is installed, you discover it's actually 2002 feet long—2 feet longer than needed. This means the rope is loose rather than taut. The rope cannot be cut, so the only options are to keep it as is or return it and order a new one.

Now there's a decision to make: keep this slightly loose rope or return it and order the correct size (which would take a considerable amount of time). The captain says he'll make his decision based on one question: if someone goes to the middle of the ship and pulls the rope upward to form a triangle, how high can the rope go?

Importantly, the captain doesn't need a precise answer or an estimate. He specifically doesn't want you to use the Pythagorean theorem for some reason he'll explain later.

So the question is: How high will the rope go if pulled upward at the midpoint?

The Surprising Answer

Now, we predict that your answer is somewhere in the range of a half a foot to a foot or two. How are we confident of that? Because we are aware of your thinking paradigm which you are not. Now there is good news and bad news with that answer. The good news is that nearly everyone's answer is in that range. Which makes the case that all of you had the same or similar model of a triangle in your mind and all of you simulated the triangle in the same or similar way, because all of your thinking is based out of the same thinking paradigm, which for lack of a better word, we will call the analytical thinking paradigm.

Now let's come to the bad news. The bad news is that the answer is wrong—not just slightly wrong, but dramatically wrong. The rope will go so high that an elephant sitting on an elephant sitting on an elephant sitting on another elephant—and possibly a baby elephant on top—can pass underneath it. The triangle will go ~44 feet high!

Now all of you are saying, "That's impossible! It makes no sense." We fully understand it makes no sense to you because in your mental simulation, you still see the triangle only going a foot or two foot tall. But before we point fingers at each other saying you're wrong and I'm wrong and get angry and justify our answer to each other, we should be able to conclude that either I am wrong or you are wrong or we both are wrong—because we can't both be right in this case. The triangle can't be two ft and 44 ft tall at the same time. If you agree with that statement, then instead of fighting over it, let's first devise and agree on a method to determine which answer is right. Fortunately, in this case, we have two ways to verify the truth. First, we could get a 2002-foot, or if that's too long then we can get a smaller 202-foot or 22-foot long rope, and test it in the physical world. Or we can use the Pythagorean theorem, which we both trust can't give a wrong answer to this problem. So if you apply the Pythagorean theorem, the answer would be 44ft and the solution is on your screen, you can do it by yourself.

The Real Learning

Now, most of you will accept this answer and move on, saying "makes sense," and let me predict, your chances of becoming a systems thinker are next to negligible because you're failing to realize that I am not here to give an answer to the triangle problem. I am here to teach you about thinking, so if you are wondering how the heck you got the answer so blatantly wrong. If you are wondering that and seeking an answer to that, you have chances of becoming a good systems thinker.

Now when we ask this question to people why they got the answer to the question wrong, many say it's because "You didn't allow us to use the Pythagorean theorem," or "You didn't give us enough time," and the list goes on but we can prove that all of those answers are nonsense answers in this context. The only appropriate answer is that either my mental model of the triangle was wrong, or the way I simulated the triangle in my mind was flawed. Unless you accept that, if you even lack that reasoning and awareness, learning systems thinking is going to be hard for you. Now if you agree that it has to be a flaw in your mental model of a triangle or how you simulated the triangle, then I have a follow-up question. Despite knowing that the triangle would go 44 ft high, in your mind the triangle is still only about 1 foot tall. Why can't you correct your mental model despite knowing it's wrong and knowing the right answer? I have given people hours and days and months and years, and people are not able to correct their mental model of a triangle that goes above two feet. We conclude that they are not able to go one level up and introspect their thinking paradigm using which they think to develop the mental model. This question is critically important because most of you don't deal with triangles in your daily life—you deal with something far more complex, more dynamic, systems with many more variables. In those cases, you neither have a physical way to simulate systems nor a mathematical formula to correct your answer. In those situations, being aware of your thinking paradigm could be your superpower for designing, operating and managing systems you are responsible for.

Taking Responsibility

So we hope we've given you an example of a situation where you have mental models and simulate those models but lack awareness of the thinking paradigm behind them. Even when you know the right answer, you can't correct your mental models. We're lucky in this case because we have the Pythagorean theorem for the correct answer, but in other situations, you don't. Therefore, even if you're someone who wants to take responsibility for your actions, you'll fail to do so because you'll have no idea that you're wrong.

So back to the difference between a Regular Thinker and a Systems Thinker:

A Regular Thinker thinks but isn't aware of the thinking paradigm they use to develop mental models and simulate those models. They can't learn or correct errors when the defect or limitation isn't in their thinking but in the thinking paradigm they use to think.

A Systems Thinker, on the other hand, is aware of the paradigm they use to develop mental models and simulate them. They understand the limitations of that paradigm and therefore seek newer thinking paradigms. They're not only much better at error correction but also at creating options and solutions that aren't available to regular thinkers because these options wouldn't fit in the regular thinker's mental model.

The Limitation of Traditional Advice

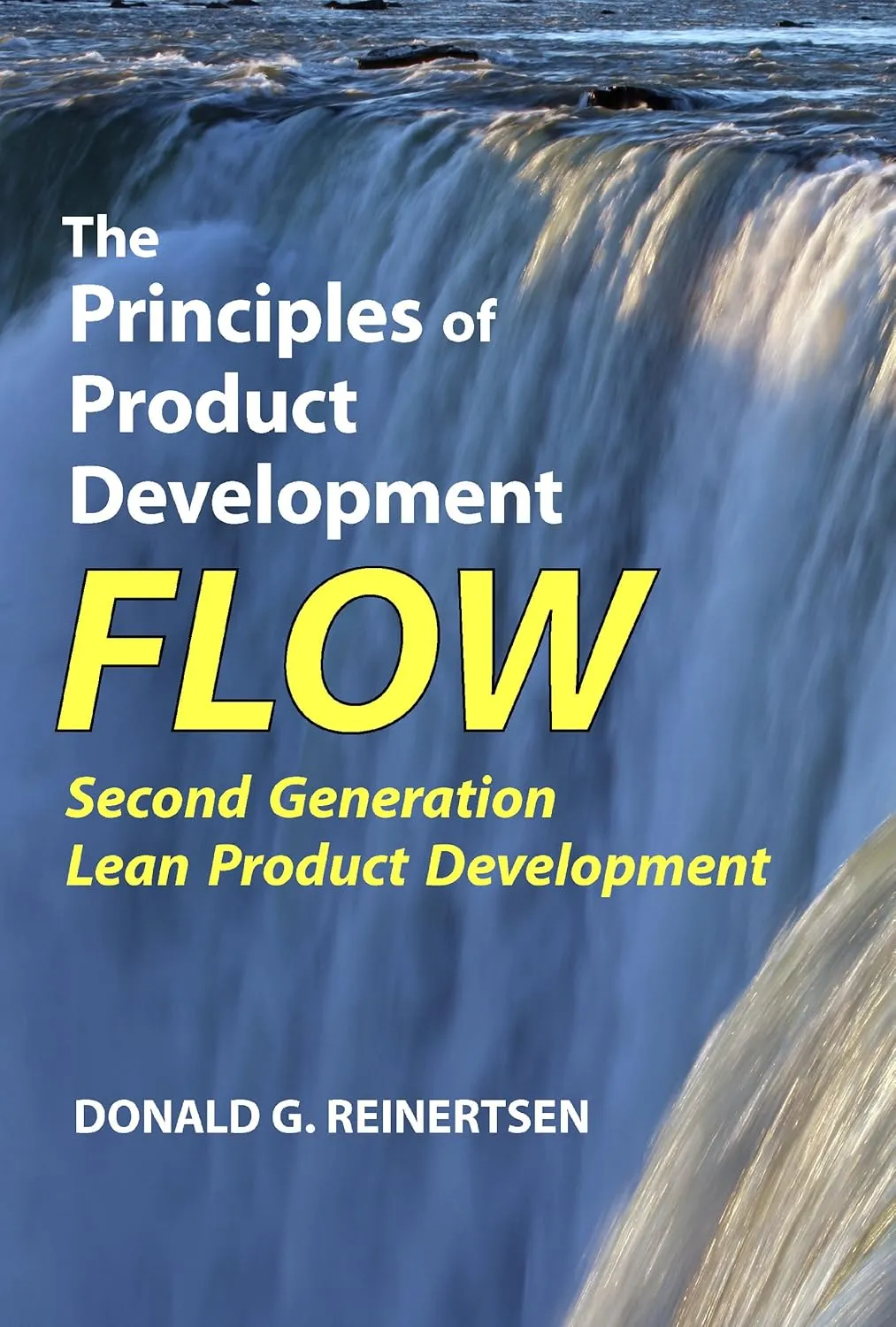

This brings up an interesting situation: For decades management books are giving you advice that "be aware," "question your assumptions," or "check your confirmation bias" and the list goes on, but none of that works most of the time because those assumptions, biases belong to your thinking paradigm and you can't be aware of what you are not aware of, at least not simply by thinking. You have to think about your thinking a.k.a. thinking paradigm, that has been harder for me and took decades to achieve on my own.

Where should you start? Don't start by self-learning here. We can already predict most of you started long ago but have not made much progress because awareness of thinking paradigm is hard to click but once it clicks, it just clicks. We suggest you coming to SystemsWay, because we don't just teach you systems thinking tools or techniques—we first make you aware of your thinking paradigm and demonstrate how that thinking paradigm fails you less with triangle questions but more with the complex dynamic world you deal in and deal with.

So if you're ready, reach out for our corporate workshops. And if the triangle in your mind still doesn't go more than 2 feet high, remember—the only solace you can get is that it doesn't for most. This means your thinking paradigm is the same as others' because we all are the outcome of the same analytical scientific education process, and we need to collectively become aware of our thinking paradigm, and collectively upgrade to newer and better thinking paradigms which you can only be aware of if you become aware of your current paradigm.

I hope we've convinced you—though perhaps we've failed you again. If we have convinced you, the ball is in your court to start the journey.

A Special Note on Thinking Paradigm, Intuition and Instincts

Many people who get the triangle question wrong defend themselves by claiming it's not their thinking that's limited, but rather their intuition that needs development. This argument, prevalent in management training circles, is fundamentally flawed because it artificially divides the mind into separate "thinking" and "intuition" systems when these are actually interdependent processes.

When someone says they're using intuition, they're actually simulating mental models to make decisions. Intuition is precisely this simulation of mental models in the mind. So when people advise "don't think, use your intuition," they fail to recognize that intuition is a form of thinking itself.

When Jeff Bezos says that after extensive analysis, he ultimately relies on his intuition for decision-making, he means he's making decisions by simulating systems and mental models in his mind. Everyone makes intuition-based decisions because everyone simulates mental systems and models. Therefore, intuition isn't superior to thinking or vice versa - they're interconnected aspects of the same cognitive process.

To improve intuition, one needs to practice better simulation of systems. However, if the underlying thinking paradigm is flawed, no amount of simulation practice will yield better results. In such cases, one needs to become aware of the thinking paradigm underlying both their analytical thinking and intuition, and seek new paradigms better suited to the problem at hand, that's when Systems Thinking abilities become a superpower.